Lot 77 of Sunnyshore Acres

In the spring of 1970, my dad, Jack, mom, Ann, and one-year-old me moved to Lot 77 of Sunnyshore Acres on Camano Island. It was Dad’s dream to be a full-time artist. Mom’s dream was to live near the farm she loved. Their dreams came true through a gift from Doc and Sayre Dodgson.

In the 1920’s Norman Bates short platted and sold lots on a large section of land he owned called Sunnyshore Acres. It stretched east from Doc’s farm all the way to Port Susan. The new owner of one of the ten acre lots turned it into a fox farm. In the 1920’s and 30’s it was vogue for socialites to wear mink and fox stoles. And, as the logging industry on Camano faded, people found ways to make money. There was money in fox pelts. The fox farm comprised a small house, a furring shed, a breeding pen, and a fox run with eight feet fences buried deep into the ground so the foxes couldn’t dig out.

After Norman died, his widow Helen married Mr. Thompson. She still owned the big house that she and Norman had built years before across from the fox farm on the bluff, with windows that looked down on Sunnyshore Acres Beach and framed the always new and fresh sunrise, the pink sky become gold as the sun peaked over the cerulean Cascades washing color over Port Susan like a watercolorist laying down a wash. Helen was a friend to Fanny Cory Cooney, who lived directly cross island. Maybe that’s how Doc learned about the opportunity. In the early 1950s, Doc purchased three ten acre lots east of the farm, including the old fox farm: Lot 77 of Sunnyshore Acres.

For many years, Doc’s hired hand, Armand Koeller and his family lived in the little white house next to the road. Doc and Armand dug out the basement by hand. They poured the foundation and basement floor as they went. After the Koellers left, other families made it home. But by the late 1960’s the house had sat abandoned for almost twenty years. Thieves stole all the saleable items, including the 400 feet of copper wiring that went to the original hand dug well. It was an empty shell except for the mice poop.

Jack Dorsey: Pioneering Artist

While working as an assistant pastor at Renton Bible Church, my dad, Jack Dorsey, sold watercolor paintings at the Burien Arts Gallery and had a successful weekend at the Bellevue Arts and Crafts Fair in the summer of 1969, making $700. Dad and Mom talked about him becoming a full-time artist. Mom, who had the blood of Fanny Y. Cory coursing through her veins, was up for a challenge. They just needed a place to live for cheap. A thought came into their minds: maybe they could move out to Camano Island and live in the vacant house owned by Doc. They inquired if they could rent. Doc and Sayre decided that they would gift each of their kids with an early inheritance. They gave Dad and Mom the ten acres with the little white house on the old fox farm. Doc’s gift helped launched Dad’s artistic career.

Their new home had an old bathroom with no fixtures, a dankly little kitchen sink with no running water, junky old cabinets, a small living room and a bedroom. The only plumbing left was a cast iron drain pipe that went into a drain field. There was no heat. No water. No electricity. “And it was dirty,” Mom says. But they loved it. It was theirs. And they were young and full of pioneering zeal and hope. It was the fall of 1969.

Because the house needed so much work and there was no heat, we lived that first winter in Helen Bates Thomspon’s house across the street. She let us stay there rent free, a favor to the family of her friend Fanny. When the weather was warm enough, Dad painted at his art table out on the enclosed big porch. In his spare time, he and mom worked on their new home. The first thing they did was clean. “I wanted it cleaned up because I had a little baby,” Mom says. She was eager to move in. As nice as the Helen’s house was and as much as they loved this kind woman, Mom dreaded seeing her car come down the drive: “I wasn’t the best housekeeper and I had a baby.”

In the spring of 1970, we moved in. There was no refrigerator so they used a wooden box that they set on the porch where it was cooler. For three years they hauled water in milk cans from the farm in Dad’s red 1968 three quarter ton pickup truck. Mom didn’t have any place to put dishes after she had dried them. Mom remembers wishing that she had a dish drainer to go on the counter to put the wet dishes in. She wished or prayed “if only I could have a dish drainer.” Not long after, Mrs. Love, one of their neighbors came down with a dish drainer. “Such a little thing but such a big gift when you have nothing,” Mom says.

Dad heated our home with an old cast iron furnace from Bob Crow that heated the house through the duct work installed by Bernie Dallman. Dad also bought a Monarch wood stove for the kitchen for twenty-five dollars from Heitmann, the father of Don, one of Ann’s classmates. Dad installed a bigger window in front of the sink that looks out towards east Camano drive and welcomes guests with the warm light of the kitchen. Mom decorated the sill with little flowers in dear glass vases from the garden she planted. She still does.

The Helping Hand of Neighbors

Friends and neighbors offered a helping hand. A few months after we moved in, two families from Renton Bible Church, the Doellefelds and Kapioskis, spent a day building a fancy two-seater outhouse two hundred feet from the house. I remember the long walk to visit it in the dark of winter. Dad or Mom’s presence and flashlight kept at bay the scary creatures of a child’s imagination.

One day a neighbor came up the road looking for his lost cow. Dad tracked it down Sandells dirt road. He got the cow to come back and, in doing so, made fast friends of Ed and Lorraine Johnson. Ed, who was a cabinet maker by trade but was “knowledgeable,” helped Dad get electrical power into the house. They put in electrical wires, a 200 amp circuit breaker and hooked up the breaker box all of this without bothering to contact the PUD. Later with the help of Robert Hale, Dad put an electric furnace in downstairs. When he turned on the electric furnace, the transformer blew and the PUD guys had to come out and put a stronger transformer. Before Jed was born in 1976, Leo Hall helped Jack install the plumbing for the bathroom.

Bill Wayland, who Dad knew from Mabana Chapel and Camano Chapel’s joint youth events, told Dad that Gordy Montgomery was remodeling his home and was willing to give Dad his old but solid kitchen cabinets made by Stanwood millworks. Dad brought the cabinets over in a flatbed truck and moved them through the backdoor and set them up in the kitchen. Ed Snowden came down with his backhoe and dug out dirt behind the house down to the foundation. Dad borrowed “Tinney” McGrath’s cat and terraced the land leveling where the nut trees are and making the slope down to the woodshed.

In 1973, Doc helped Dad get the old well up and running, Dad installed plumbing, and we had running water. But then we had well trouble. Ted Snowden, who lived south of us and had a well digging operation, helped Dad out with the well originally hand dug by Andy Wall. It was one hundred and fifty feet deep, but the bottom of the well didn’t have much water in reserve since the well diggers had to stop when they hit water. The well had a reciprocal pump at the top with two-inch piping to draw the water up. Within the pipe were steel rods that screwed together in twenty-foot sections. At the bottom of the steel rods was a leather suction mechanism. When the leather sucking mechanism got gunked up with sand, the steel rods had to be pulled up and the leather mechanism cleaned.

Pulling up the steel rods was a VERY traumatic ordeal. Dad recruited me to help dad because mom – who is usually a very capable and courageous woman – absolutely refused to assist Dad on this job. After a time or two I likewise refused. The steel rods were very heavy. Dad would strain and grimace as he pulled them up. When he was able to unfasten one of the twenty-foot steel rods he would say in a strained and stressed voice. “Clamp it! Hurry Jason, clamp it!” At that point I was supposed to close a vice grip on the rod that was left hanging in the two-inch pipe, so it wouldn’t fall into the well and be lost forever. Dad would unfasten a twenty-foot section of the steel rod, and we would do it again, Dad grimacing and yelling to “hurry up” as I tried to fasten the vice grips so that our well wasn’t ruined. Such were the ordeals of our pioneer artist family.

Thankfully, Ted came to the rescue. He suggested that Dad ought to put a jet pump in the well. Probably because he had run out of recruits to help him, Dad decided to do just that, and Ted Snowden helped put in the jet pump. It made a huge difference. Ted also suggested that we get that big reservoir. Those two things changed our lives.

The Fence

Dad built a tall wood fence between our house and the road. Apparently at the early age of two and three I was a “runner” just like mom; an “adventurer,” as Mom puts it. I would dash down the logging trail to the farm. The grass was tall and mom could just barely see my blonde head, hair bouncing as I ran down the hill. Mom says that she stayed slim that summer from racing after me. I suppose she preferred me running through the woods to the farm rather than running up the road to the neighbors in the house south and across the street from us. We had wonderful neighbors who lived there: Mr. and Mrs. Cashner, then Mr. and Mrs. Love, then Pat and Peanut Burke, then Peanut’s sister Robin and her husband Ross Robinson, with their children, Randi, who was in my class at Stanwood, Laura, Autumn and Amber.

Mom tried to keep track of me but in one minute I could disappear. Once Mom lost track of me. She raced down the logging trail. Dad canvassed the road and the yard. When she couldn’t find me, Mom raced back. There I was back at the house and Dad visiting with Mrs. Cashner. It turned out that Mrs. Cashner had looked out her window and seen a little boy in her yard. Realizing who I was, she brought me home. For Mom, the scariest time was when I disappeared one day and she went around the fence to check the road first. I was on the other side of the road. A logging truck filled with logs was barreling down the road just seconds away. She didn’t have time to cross and she feared that I would come to her. Mom says, “I yelled at you ‘stay’ and you did and the big logging truck went by at fifty miles an hour. It is the grace of God that you are still alive.” The old fence didn’t work perfectly but it still stands, kind of, propped up by ivy and other vines that Mom planted.

Basement Studio

For a while Dad set up his studio in the unfinished basement. To get to the studio you had to walk out the door and down an incline. Dad hung some lights, set up his desk and easel and started painting. It was snowing on March 25, 1972, the day when my younger sister April was born. Instead of rushing to Doc and Sayre’s home for the home delivery, Dad painted the scene he saw through the basement doors: bright patches of snow on the two apple trees and snow dusting the cedar blocks, with the Prussian blue and green of the firs the dark values beyond. He called it “The Day April was born.” I’m sure it was beautiful. I’ve always loved his watercolors, fresh and sparkly. Thankfully he made it in time for the delivery but barely.

There is another humorous story tied to the basement studio. The O’Briens, who were family friends and who owned the Turkey House restaurant at Island Crossing, let Dad hang his paintings and didn’t take a commission. Diners would see the paintings and Dad’s business card and get in touch with him, some even visiting – to our great dismay – the basement studio. Once two gentlemen were looking over the artwork. One of the men went outside to smoke. He came back in quickly. He said that the little boy outside had told him that, “He shouldn’t smoke. It’s not good for you.”

Sunnyshore Studio

With its poor lighting the basement wasn’t going to be a long-term solution. So Dad turned the fox shed into a studio. He tore out the old floorboards and a section of cement flooring, shored up the foundation, brought water and electricity to the shed, put down floorboards, put in a sink and sheetrock, added an electric heater. He moved into his new studio in 1976, the same year my brother Jed was born. Mom had learned her lesson. Jed was born at the University of Washington on July 7, 1976. Dad called it Sunnyshore Studio because it was part of Sunnyshore Acres and because, as he puts it, “the name sounds happy.” Fancy business cards displayed the new name.

Even with a studio making it as an artist was still a grind. Dad sold his art wherever he could, but mainly at the Turkey House restaurant. When the Turkey House was franchised, with eight restaurants up and down I-5, Dad would have up to seventy paintings in circulation. He also sold at a bank in Redmond and at the Creative Eye Gallery in Friday Harbor. A wealthy friend of his brother Chuck Bay hosted a house party to sell his art. And he had two shows at the prestigious Frye Art Museum, Seattle. The first in 1972 and the second in 1979. He also had a one man show at the Franell Art Gallery in Tokyo, Japan where he sold all eighteen paintings in the show. That was a boon. But mostly we scraped by.

Bobbie Mueller and the Beginning of Mom’s Art Career

Mom hustled to make money selling art too. She wanted to buy a set of toys for her growing family that she discovered on a visit to neighbors Rudy and Bobbie Mueller’s home. The Mueller’s were special because they lived close, just southwest of the farm, and had kids: Victor, Sabina, and Mark, who was a year older than me. One day, Mom visited with me in tow and Bobbie invited us in. Mom saw this most wonderful toy made by Fisher Price, a house that folded up and that had the little furniture and little people. Worried about me playing exclusively with the two toy guns Dad had made me and wanting toys more “relational and cultured,” Mom set her heart to buy not just the house but the entire Fisher Price series of wonderful buildings that included a house, a castle, a barn, etc, and the figures that came with them. Of course, we didn’t have the money for this, but mom was not to be dissuaded.

To earn money for the Fisher Price set, Mom took up watercolor, painting on the Bristol board that Fanny had used for her comic strips. Mom found that watercolor on Bristol paper was forgiving and perfect for her washes and soft pastel colors. She painted a few commissions of children, and lots of birds and flowers, her favorite subjects. She sold most of her paintings to her mom, Sayre, who bought them for wedding presents. As Mom got serious about her watercolor painting, she decided to take the name Ann Cory. Cory was her grandma’s maiden name and Mom’s middle name. Plus she didn’t want to get into shows on Dad’s coattails.

She still teases Dad about one art show. To enter art shows then you had to take the framed original in to be juried. Mom figured since Dad was hauling paintings to the Edmonds Art Festival jury, she would enter two also. They waited for the notice. When Dad tore open his envelope, he saw that his paintings had not been accepted. But both of Mom’s had, and she even won a fifty-dollar prize. She still likes to rub it in. Dad takes it pretty well. She probably used that money to buy the castle set that I remember having so much fun playing with.

Mexican Fighting Chickens

Making it didn’t require making money. You could “live off the land.” To live off the land for a while we raised Mexican Fighting Chickens. A friend gave them to us. We gave them away to some other neighbors, after a good bit of trauma.

They were free-ranging. At night they roosted in the rafters of the workshop area of the old-fox-shed-converted-to-art-studio. They made a good night of sleep hard. In the middle of the night, there would be a terrible squaking. Dad would grab his gun, and race out to take a shot at the racoon or possum that was causing the racket by trying to eat them. During the day they would sit on their nests and raise the cutest chicks or scratch in Mom’s gardens. There were a couple of rooster fights too. But the roosters were beautiful in scarlet and orange and bravado. I do remember the day we butchered one. Dad brought me along for moral support. Mom was nowhere to be found. After somehow catching it, which was a minor miracle because they were so fast, Dad put the neck over the chopping block and WHAP. What I do remember is what happened next. The headless chicken ran like crazy. It was awful. I can see it still in my memory today galloping around for what seemed like an hour, but was probably only thirty or forty seconds until it kind of tottered and fell on its side. Dad dressed it and Mom put it in the freezer. But we never ate it.

Not long after the beheading we gave the “outstanding” Mexican Fighting Chickens away to the Yazels. Catching them was another trauma: Dad and John Yazel sprinting after them, the chickens scrambling every which way, the roosters running with their head and feet parallel to the ground at forty miles an hour or so.

The Yazels were good neighbors. There was John and Karen and David, Zachary, and Courtney. One Sunday they joined Doc and Sayre at our home for dinner. The kids were running around like Mexican Fighting Chickens and Zachary skid on the old wood floor on his knee and got a terrible splinter. Doc was there and had his doctor’s bag in the car. Zachary was put on the kitchen table. The surgery lasted an hour. Grandpa cut to find the sliver, then, puzzled, cut a little more. He couldn’t find it so he bandaged it up. When Zach was brought to Doc’s office in Stanwood to get the bandage changed, Doc wiped his knee with a sterile sponge and lo and behold there was the large splinter on the sponge.

Home Schooled

Pioneering was a great education for a boy. But as I got to school age, mom thought I should get a “proper” education. She asked Bob and Marilyn Finke how they home schooled their kids. They were missionaries in Mexico and Columbia, South America. They didn’t send their kids to boarding school like many missionaries did. Instead they used an official course that involved sending homework to real teachers who were paid for their help. Mom signed us up. Thus began the ordeal for Mom and me. Mom took it very seriously. She was going to raise the perfect son. She tried to stick by everything, and still give me lots of free time. Best of all, we always went to the Sno Isle bookmobile that every other week had a stop at the farm. We’d head home with boxes of books. Since then reading has been my strength.

Mom and I made it through 1st grade. But we weren’t bringing out the best in each other. In second grade, things got worse, and I, determined and willful, was bringing out the worst in both of us. Mom made arrangements to take me to Stanwood Elementary. She just wanted to be my mom, not my teacher. She says, “I knew I was treating you worse than I would treat other kids and you were treating me worse than you were treating other adults.” The day came when Mom and Dad got me in the van. When we pulled into the parking lot with the school buses I hid on the van floor hoping to not be seen by other kids. I didn’t know anyone. I didn’t want to go in. Thankfully, I was assigned Ms. Guild who welcomed me to the class with open arms. She asked a classmate, Mike Case, to show me around the school. I flourished in the public school system.

The Cedar Shake Roof

We survived by hard work and thrift. Firewood to feed the stoves was free. The annual rhythm was cutting, splitting and stacking firewood. In 1974, Dad asked Dan Garrison at his former real estate office in the Country Club if he could cut wood for his stoves from his logged off land south of Camano Hill road, now Michael Way, and Dan agreed. When cutting wood, Dad discovered old growth cedar stumps all over and he concentrated on cutting twenty-four inch bolts of cedar that had been blackened by fire but were still in good shape. He hauled load after load home and stacked the cedar bolts planning to make cedar shakes to use on the roof in the future. He often brought me along with him for this work.

Through the 70’s and early 80’s, the shingle roofed house had lots of leaks. Dad was always climbing up on the roof to patch the leaks. In 1984, when he had an addition built on the house, he decided the time was right to install a cedar shake roof made from the bolts. Dad split shakes with a tool called a “froe.” It had a wooden handle at right angles to a steel blade used to cut through cedar bolts. He would use a draw knife to smooth the shakes into a taper, but generally every time he cut a shake, he would turn the bolt which gave a natural taper to the shake. April, Jed and I helped a lot with the shaping and stacking of the shakes. And when it came time to install the shake roof lots of people pitched in, including cousins from the farm – Doug, Bruce, Derek and Ethan. My friends Harry and Steve chipped in too. The new roof was finished the summer of 1984.

The New Sunnyshore Studio

In 1998, Jenny and I were living in Seattle where I was serving as pastor of a presbyterian church. We couldn’t afford to buy in Seattle. Dad and Mom, like Doc Dodgson had done so many years before, gifted us with a piece of property with a small dilapidated cottage just 200 feet south of their home. It was the place our wonderful neighbors had lived so many years before. I tore the dilapidated cottage down, had the land graded, and dreamed of building an art studio and gallery that would showcase our family of artists.

But our family had moved to Indianapolis, IN and it didn’t seem practical to run an art studio from there. Then in January 2015, Mom called and said she had been diagnosed with breast cancer. Tectonic plates in my heart shifted. Though we were locked into our life and my pastoral calling in Indy, I thought that I would like to be close to Dad and Mom to care for them in this stage of life. I took a pastoral call in Redmond, WA. And in March of 2016, I broke ground on a long-dreamed of art studio. Since our grand opening in December 2016, the new Sunnyshore Studio has showcased our family of artists.

In June 2019, we held an auction of Dad’s paintings as part of a “Raise the Roof” project to replace the old cedar shake roof which by then was thirty-four. Friends and family, collectors and patrons of Dads bought over 21K of art and Dad and Mom got a new roof. We salvaged all the good old shakes and used them for siding on the new well house that is close to their home. It was a joy for me to be able to support and honor Dad for what is now over fifty years of hard work as a pioneer artist on Camano.

Pioneer Artist Family

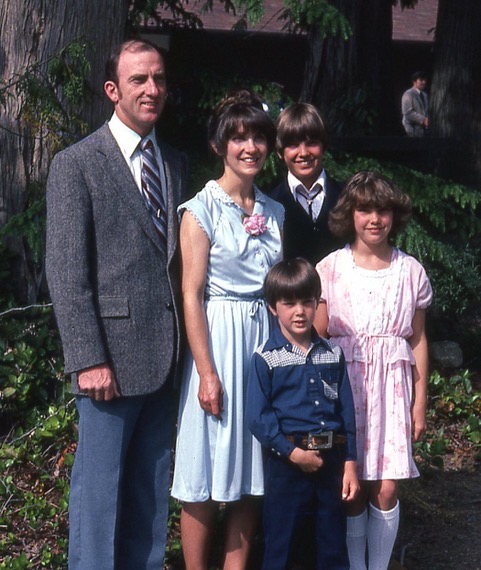

Camano is an island of artists. I suppose that our family of artists, now with five generations of artists who have lived on and loved Camano stretching all the way back to my illustrious great-grandmother, Fanny Y. Cory Cooney, whose story I will share later, have contributed to the aesthetic riches of this place. I know Dad and Mom’s courage to carve out a life as a pioneer artists impacted their kids. I find joy in painting as a pastime and in showcasing our family of artists at the new Sunnyshore Studio that I co-lead with my wife, Jenny. My sister, April, who lives on a beautiful farm on Camano, may be the most talented artist of the siblings; I wish she could find time to paint more. My brother Jed, who lives in Camaloch, followed in Dad’s footsteps. He’s a full-time artist and the director of the very successful Acrylic University, an online platform with students from all over the world. April, Jed and I all have children who are emerging artists. We look back to Dad and Mom pioneering as artists on Lot 77 as the birthplace of our creativity and passion to share beauty with the world.